RT systems software underpins the functionality of numerous critical applications, from industrial automation to aerospace systems. This exploration delves into the core principles, design considerations, and future trends shaping this vital field. We will examine the distinctions between hard and soft real-time systems, explore suitable programming languages and tools, and discuss the architectural nuances that ensure optimal performance and reliability.

The development of robust and efficient RT systems demands a deep understanding of scheduling algorithms, error handling mechanisms, and rigorous verification processes. This overview aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the challenges and opportunities presented by this increasingly important area of software engineering.

Defining RT Systems Software

Source: ibb.co

Real-time systems software demands precise timing and resource management, a stark contrast to the more forgiving nature of applications like tax software. For example, consider the complexities involved in managing financial data, as seen in the h&r block tax software deluxe + state 2022 , compared to the stringent requirements of embedded systems. The differences highlight the varied challenges faced in software development across different domains.

Real-time systems (RTS) software is a specialized type of software designed to react to input events within a predetermined timeframe. Unlike general-purpose software that prioritizes functionality and efficiency, RTS software emphasizes timely responses, often with critical consequences associated with delays. Its core purpose is to control and manage devices or processes that demand immediate action.

Real-time systems software’s core functionalities revolve around managing resources efficiently to meet stringent timing constraints. This includes scheduling tasks to ensure deadlines are met, handling interrupts promptly, and managing system resources such as memory and processors effectively. It also involves incorporating mechanisms for handling errors and failures gracefully, minimizing the impact of unexpected events on the system’s timely operation. Furthermore, real-time software frequently integrates closely with hardware, often requiring direct access to hardware peripherals for control and monitoring purposes.

Hard and Soft Real-Time Systems

Hard real-time systems require that all deadlines be met. Failure to meet a deadline in a hard real-time system is considered a system failure. These systems are typically found in safety-critical applications where a missed deadline could have catastrophic consequences. Soft real-time systems, on the other hand, prioritize meeting deadlines, but missing a deadline does not necessarily lead to system failure. Instead, performance degradation or reduced quality of service is more likely. The difference lies in the severity of the consequences associated with missed deadlines.

Examples of RT Systems Software Applications

Real-time systems software finds applications across a wide range of industries. In the automotive industry, anti-lock braking systems (ABS) and electronic stability control (ESC) rely on RT software to react instantly to changes in vehicle dynamics. In industrial automation, robotic control systems use RT software to coordinate the movements of robots in manufacturing processes. Air traffic control systems depend on RT software to manage air traffic flow and prevent collisions. Medical devices, such as pacemakers and anesthesia machines, utilize RT software to provide precise and timely control of critical functions. Furthermore, telecommunications networks employ RT software to manage network traffic and ensure low latency for voice and data communication.

Architectural Models for RT Systems

Several architectural models exist for designing real-time systems. One common model is the monolithic architecture, where all system components reside in a single process. This simplifies development but can be less robust and scalable. Another is the microkernel architecture, where essential system services reside in a small kernel, while other services run as separate processes. This offers improved modularity, reliability, and scalability. A further model is the layered architecture, which organizes system components into layers based on their functionality. This approach promotes code reuse and facilitates system maintenance. The choice of architecture depends on factors such as system complexity, performance requirements, and reliability needs. Each model presents trade-offs between complexity, performance, and maintainability.

Programming Languages and Tools

The selection of appropriate programming languages and tools is crucial for the successful development of real-time systems (RTS). The stringent timing requirements and often safety-critical nature of these systems demand careful consideration of factors such as determinism, efficiency, and code reliability. The right tools can significantly improve developer productivity and reduce the risk of errors.

Programming Language Suitability for Real-Time Systems

Several programming languages are commonly employed in real-time systems development, each with its own strengths and weaknesses. C remains a dominant choice due to its low-level access to hardware, predictability, and efficiency. C++, while offering object-oriented features, can introduce complexities that might hinder real-time performance if not carefully managed. Ada, designed specifically for high-reliability systems, provides strong typing and built-in concurrency features that enhance safety and reduce errors. The choice often depends on the specific requirements of the application, balancing performance needs with development time and maintainability considerations. For instance, a safety-critical aerospace application might favor Ada’s robust features, while a less critical embedded system might find C sufficient.

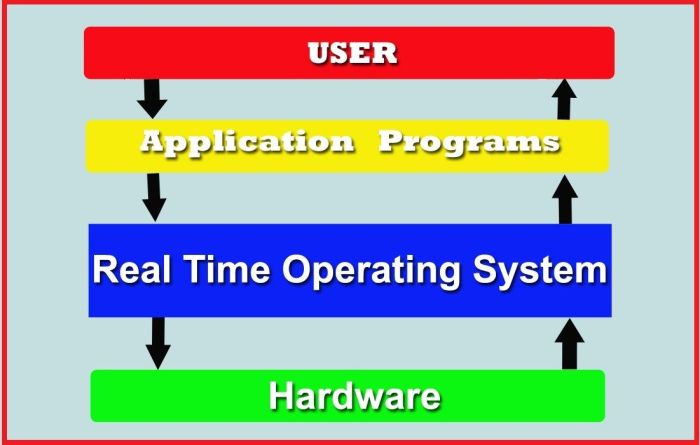

Features and Benefits of Real-Time Operating Systems (RTOS)

Real-Time Operating Systems (RTOS) provide a structured environment for managing tasks and resources in real-time applications. Key features include preemptive multitasking, allowing the system to switch between tasks rapidly, interrupt handling for immediate response to external events, and resource management to ensure efficient allocation of memory and other resources. The benefits of using an RTOS include improved system responsiveness, enhanced determinism (predictable timing behavior), and simplified software development through task scheduling and synchronization mechanisms. These features contribute to the reliability and predictability essential for real-time applications, enabling them to meet their strict timing constraints. For example, an RTOS might prioritize a task responsible for controlling a braking system in a vehicle, ensuring timely execution regardless of other ongoing tasks.

Debugging and Testing Tools for Real-Time Systems

Effective debugging and testing are critical for ensuring the correctness and reliability of real-time software. Common tools include logic analyzers for observing signal timing and interactions, in-circuit emulators (ICEs) for real-time debugging at the hardware level, and specialized debuggers integrated with RTOS environments. These tools enable developers to monitor system behavior, identify timing issues, and trace program execution, significantly reducing the time and effort required for troubleshooting and validation. Furthermore, simulations and model-checking techniques can be used to verify the correctness of the system design before implementation, thereby preventing potential problems early in the development lifecycle. For example, a logic analyzer can pinpoint timing anomalies in a communication protocol, while an ICE allows stepping through code execution on the target hardware.

Comparison of Popular RTOS Options

| RTOS | Features | Licensing | Target Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| FreeRTOS | Lightweight, preemptive multitasking, inter-process communication | MIT License | Embedded systems, IoT devices |

| VxWorks | High-performance, real-time capabilities, extensive networking support | Commercial | Aerospace, industrial automation |

| QNX | Microkernel architecture, POSIX compliance, safety certification | Commercial | Automotive, medical devices |

| RT-Thread | Scalable, open-source, supports various architectures | GPLv2 | Embedded systems, IoT devices |

System Design and Architecture

Designing a robust and efficient real-time system requires careful consideration of its architecture. This involves defining the system’s components, their interactions, and the overall structure to meet the stringent timing constraints and reliability requirements inherent in real-time applications. A well-defined architecture facilitates development, testing, and maintenance.

This section details the design of a basic real-time control system for a robotic arm, illustrating key architectural principles and component interactions. We will explore a hierarchical structure for the system’s hardware and software components and visualize the modular interactions through a flowchart. The role of scheduling algorithms in optimizing performance and resource utilization will also be examined.

Robotic Arm Control System Architecture

The architecture for a robotic arm control system can be organized hierarchically, separating tasks based on their timing requirements and functionalities. This layered approach enhances modularity, maintainability, and allows for independent development and testing of individual components. The system can be broadly divided into three layers: the hardware layer, the low-level control layer, and the high-level control layer.

The hardware layer comprises the robotic arm itself (motors, sensors, actuators), microcontrollers, and communication interfaces (e.g., Ethernet, CAN bus). The low-level control layer is responsible for direct interaction with the hardware, managing motor control, sensor readings, and basic safety functions. This layer typically runs on a real-time operating system (RTOS) and utilizes low-level programming languages. The high-level control layer focuses on higher-level tasks such as path planning, trajectory generation, and user interaction. This layer often runs on a more general-purpose operating system and might utilize languages like Python or C++.

Component Interaction Flowchart

A flowchart visually represents the interactions between different modules within the system. In our robotic arm example, the flowchart would depict the flow of data and control signals between the different layers. The high-level control layer sends commands (e.g., desired position and orientation) to the low-level control layer. The low-level control layer processes these commands, translates them into motor control signals, and monitors sensor feedback. Sensor data is then fed back to the high-level control layer for closed-loop control and adjustment. Error handling and safety mechanisms are integrated at each layer to ensure system stability and prevent unexpected behavior. For instance, a sensor detecting an obstacle would trigger an immediate stop command, passed down through the layers.

Scheduling Algorithms in Real-Time Systems

Scheduling algorithms play a crucial role in optimizing the performance and resource utilization of a real-time system. They determine the order in which tasks are executed, ensuring that critical tasks meet their deadlines. Various scheduling algorithms exist, each with its own strengths and weaknesses. For instance, Rate Monotonic Scheduling (RMS) assigns priorities based on task periods, while Earliest Deadline First (EDF) prioritizes tasks with the closest deadlines. The choice of scheduling algorithm depends on the specific requirements of the application, including task characteristics, resource constraints, and the desired level of performance. For the robotic arm system, a preemptive, priority-based scheduling algorithm like EDF could be suitable, prioritizing critical control tasks over less time-sensitive tasks. Careful consideration of task deadlines and resource contention is vital for effective scheduling and ensuring system stability.

Challenges and Considerations

Developing and deploying real-time systems (RTS) software presents unique challenges stemming from the inherent need for precise timing and efficient resource management. These challenges necessitate careful consideration throughout the entire software development lifecycle, from initial design to final deployment and maintenance. Failure to address these challenges can lead to system instability, performance degradation, and even catastrophic failures with potentially severe consequences.

Timing Constraints and Resource Limitations

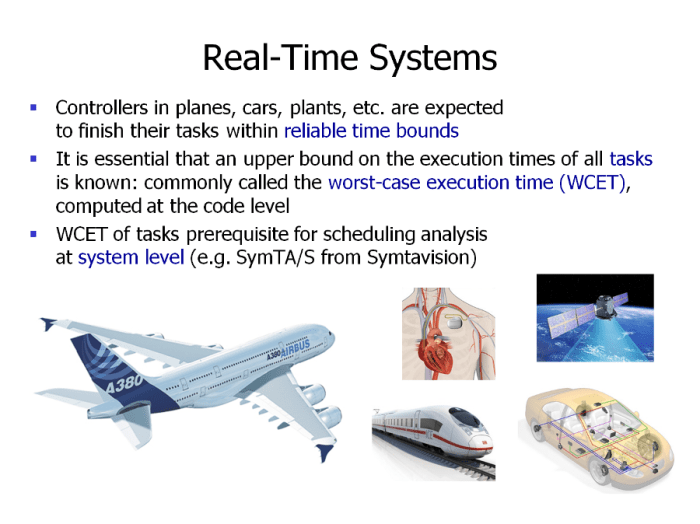

Real-time systems are defined by their strict timing requirements. Tasks must complete within specified deadlines, otherwise, the system may malfunction or produce incorrect results. This poses a significant challenge in software design, requiring careful scheduling and resource allocation to ensure that all critical tasks meet their deadlines. Resource limitations, including memory, processing power, and bandwidth, further complicate matters. Efficient algorithms and data structures are crucial to minimize resource consumption and prevent system overload, especially in resource-constrained environments like embedded systems. For instance, a flight control system must respond to sensor inputs within milliseconds; exceeding these deadlines could lead to disastrous consequences. Similarly, a medical device monitoring vital signs must process data and provide feedback within strict time limits to ensure accurate and timely treatment.

Ensuring Reliability and Safety

The reliability and safety of real-time systems are paramount, especially in safety-critical applications. Techniques like redundancy, fault tolerance, and error detection are employed to enhance system robustness. Redundancy involves incorporating multiple components or systems to provide backup in case of failure. Fault tolerance enables the system to continue operating even when some components fail. Error detection mechanisms, such as checksums and parity checks, help identify and mitigate errors. Formal methods, such as model checking and theorem proving, can be used to verify the correctness and safety of the system design. For example, the use of triple-modular redundancy (TMR) in aerospace systems ensures that a single component failure does not compromise the entire system.

Error Handling and Exception Management

Real-time systems must handle errors and exceptions gracefully to prevent system crashes and maintain operational integrity. Effective error handling strategies involve mechanisms for detecting, isolating, and recovering from errors. Exception handling techniques allow the system to respond to unexpected events without compromising the overall system functionality. In real-time environments, the speed of error recovery is critical, requiring efficient algorithms and data structures. For instance, a banking system must handle transaction failures without causing data corruption or system downtime. A sophisticated error logging and reporting system allows for post-mortem analysis and continuous improvement.

System Verification and Validation

Verifying and validating real-time systems require a rigorous approach that encompasses various techniques. Verification focuses on ensuring that the system meets its specified requirements, while validation confirms that the system satisfies the user’s needs and expectations. Methods include simulation, testing, and formal verification. Simulation involves creating a virtual model of the system to test its behavior under different conditions. Testing involves executing the system in a controlled environment to identify potential defects. Formal verification uses mathematical techniques to prove the correctness of the system design. Different approaches exist, including unit testing, integration testing, and system testing, each focusing on different aspects of the system. The choice of verification and validation methods depends on the criticality of the application and the available resources. For instance, a medical device would require a more rigorous verification and validation process compared to a simple consumer electronics device.

Future Trends and Developments

Source: absint.com

The field of real-time systems (RTS) software is poised for significant advancements, driven by the convergence of several powerful technological trends. We can expect to see not only incremental improvements in existing RTS applications, but also the emergence of entirely new application domains enabled by these innovations. The increasing demand for responsiveness, reliability, and safety in various sectors will further accelerate these developments.

The integration of emerging technologies like artificial intelligence (AI) and the Internet of Things (IoT) is fundamentally reshaping the landscape of RTS software. This integration necessitates the development of new architectural patterns and programming paradigms to effectively manage the complexity and data volume inherent in these interconnected systems. The resulting systems will be more intelligent, adaptable, and capable of handling unprecedented levels of concurrency and data flow.

Impact of AI and IoT on RT Systems Design

AI’s influence on RTS design manifests in several ways. Machine learning algorithms can be embedded within RTS to enable adaptive behavior, predictive maintenance, and improved decision-making capabilities. For example, in autonomous vehicles, AI algorithms process sensor data in real-time to control acceleration, braking, and steering, requiring extremely low latency and high reliability. Similarly, IoT devices generate vast amounts of data that require real-time processing for applications like smart grids, industrial automation, and remote healthcare monitoring. The challenge lies in efficiently processing this data while maintaining the stringent timing constraints of the RTS. This often involves leveraging distributed computing architectures and specialized hardware acceleration. Consider the example of a smart factory: sensors on machines generate data about their performance; AI algorithms analyze this data in real-time to predict potential failures and optimize production schedules, all within the confines of a highly responsive RTS.

Novel Applications of RT Systems

The application of RTS extends far beyond traditional domains. We are witnessing a surge in RTS adoption in areas like:

- Advanced Robotics: Real-time control of complex robotic systems, including those used in surgery, manufacturing, and exploration.

- Extended Reality (XR): Providing seamless and responsive experiences in virtual, augmented, and mixed reality applications.

- Financial Technologies (FinTech): High-frequency trading, algorithmic trading, and real-time risk management systems.

- Smart Cities: Managing traffic flow, optimizing energy consumption, and enhancing public safety through real-time data analysis.

These applications demand sophisticated software architectures, robust error handling mechanisms, and efficient resource management techniques.

Emerging Trends in RT Systems Software Development

The future of RTS software development is marked by several key trends:

- Increased use of formal methods: Employing formal verification techniques to ensure the correctness and reliability of RTS software.

- Adoption of model-driven development: Using models to design, simulate, and generate RTS software, improving productivity and reducing errors.

- Focus on safety and security: Implementing robust mechanisms to prevent software failures and protect against cyberattacks.

- Growing importance of cloud computing: Leveraging cloud resources for scalability, flexibility, and cost-effectiveness in RTS deployment.

- Integration of AI and machine learning: Embedding AI and ML capabilities into RTS to enhance performance, adaptability, and decision-making.

Last Recap: Rt Systems Software

In conclusion, RT systems software represents a critical component of many modern technologies. Understanding its intricacies, from the selection of appropriate programming languages and RTOS to the implementation of robust error-handling mechanisms, is essential for developing reliable and efficient systems. As technology continues to advance, the role of RT systems will only grow more significant, demanding continuous innovation and refinement in design and implementation.