Clean code a handbook of agile software craftsmanship – Clean Code: A Handbook of Agile Software Craftsmanship delves into the art of writing efficient, readable, and maintainable code. This exploration examines the core principles of clean code, illustrating how adhering to these practices significantly benefits software projects. We’ll explore various perspectives on what constitutes “clean code,” providing concrete examples of both problematic and improved code structures. The journey will cover topics ranging from meaningful naming conventions and effective commenting to mastering functions, classes, error handling, and robust testing methodologies.

The book’s practical approach, supported by numerous examples and refactoring exercises, equips developers with the tools to elevate their coding skills and contribute to higher-quality software. We will examine common “code smells,” demonstrating how to identify and refactor them for improved readability and maintainability. The ultimate goal is to foster a deeper understanding of how to write code that is not only functional but also elegant, sustainable, and a pleasure to work with.

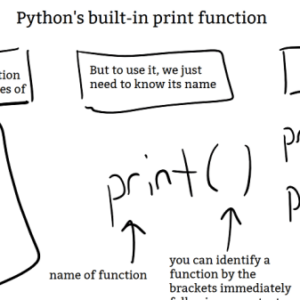

Introduction to Clean Code Principles: Clean Code A Handbook Of Agile Software Craftsmanship

Source: realtoughcandy.com

Clean code, as advocated in Robert C. Martin’s “Clean Code: A Handbook of Agile Software Craftsmanship,” transcends mere functionality; it emphasizes readability, maintainability, and ultimately, the longevity of a software project. It’s about writing code that is easy to understand, modify, and debug, even years after its initial creation. This approach prioritizes the long-term health of the project over short-term gains in speed of development.

Clean code principles aim to reduce complexity and improve collaboration among developers. Adhering to these principles leads to significant benefits, including reduced debugging time, easier code maintenance, improved team productivity, and a higher overall quality of the software product. A well-structured, clean codebase fosters better understanding, enabling quicker onboarding of new team members and facilitating seamless collaboration. This translates directly into cost savings and faster time to market.

Different Interpretations of Clean Code

While the core tenets of clean code remain consistent, interpretations can vary based on specific programming paradigms, team preferences, and project contexts. For example, a functional programming approach might prioritize immutability and pure functions, resulting in a different style of clean code compared to an object-oriented approach that focuses on encapsulation and well-defined classes. Despite these stylistic differences, the underlying goal – creating easily understandable and maintainable code – remains the same. The emphasis shifts between focusing on conciseness and explicitness, depending on the context and developer preferences. A common ground is always found in prioritizing readability and maintainability.

Examples of Clean and Unclean Code

The following table illustrates the contrast between code that violates clean code principles and its refactored, cleaner equivalent.

| Original Code | Problem | Refactored Code | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Unnecessary temporary variable temp, making the code less concise and readable. |

|

Removed unnecessary variable, resulting in more concise and readable code. |

|

God class: User class contains too many responsibilities, making it difficult to maintain and understand. |

|

Broke down the User class into smaller, more manageable classes with specific responsibilities, improving organization and maintainability. |

Meaningful Names and Comments

Clean code prioritizes clarity and maintainability. Meaningful names and well-crafted comments are fundamental to achieving this. They act as a bridge between the code’s mechanics and the programmer’s intent, improving readability and reducing the cognitive load for anyone interacting with the codebase. This section explores best practices for naming conventions and effective commenting strategies.

Choosing descriptive names for variables, functions, and classes is paramount. A well-chosen name instantly conveys the purpose and function of the element, minimizing the need to delve into the code itself to understand its role. Similarly, comments should enhance understanding, not simply reiterate the code’s functionality. They should explain the *why*, not the *what*. Effective comments provide context, clarify complex logic, and document design decisions. Overuse of comments, however, can clutter the code and hinder readability, while insufficient documentation leaves maintainers struggling to understand the code’s purpose and function.

Descriptive Naming Conventions

Effective naming follows several key principles. Names should be concise yet descriptive, accurately reflecting the element’s purpose. Avoid abbreviations or jargon unless they are widely understood within the project’s context. Use consistent capitalization styles (e.g., camelCase, snake_case) to enhance readability. The following examples illustrate good and bad naming practices.

Clean Code: A Handbook of Agile Software Craftsmanship emphasizes writing readable and maintainable code, a stark contrast to the often messy realities of web development. Understanding this principle is crucial, even when working with tools like Dreamweaver; consider this point when you check out the article on dreamweaver is an example of ________ software. Ultimately, the book’s principles help developers create robust applications, regardless of the specific software used in the process.

- Good Examples:

customerName(clear and descriptive)calculateTotalAmount()(clearly states the function’s purpose)OrderProcessingService(conveys the class’s role)

- Bad Examples:

custNm(too abbreviated)calcTot()(unclear and cryptic)OPS(meaningless without context)

Effective Commenting Strategies

Comments should clarify the *intent* behind the code, not simply restate what the code already says. They are most valuable when explaining complex algorithms, documenting design decisions, or clarifying non-obvious code behavior. Avoid commenting obvious code; let the code speak for itself. Keep comments concise and focused, using clear and precise language. Outdated comments are worse than no comments at all, so ensure comments are kept up-to-date with code changes.

- Good Comments: Comments explaining the rationale behind a particular algorithm or design choice. For example, a comment explaining why a specific sorting algorithm was chosen over another, highlighting its performance advantages in a specific scenario.

- Bad Comments: Comments that simply restate the obvious functionality of the code. For example, a comment saying “// adds two numbers” above a line of code that clearly shows `result = num1 + num2;`.

Balancing Comments and Code Clarity

The ideal balance lies in writing enough comments to guide understanding without overwhelming the code with unnecessary verbosity. Excessive comments can obscure the code’s structure and make it harder to read. Insufficient comments leave the code open to misinterpretation and make maintenance challenging. Strive for a balance that prioritizes clarity and maintainability. A well-structured, self-documenting codebase often requires fewer comments. Consider using meaningful names and clear code structure as the primary means of conveying information before resorting to comments. If you find yourself writing many comments, it may be a sign that the code itself needs refactoring for better clarity.

Functions and Methods

Functions and methods are the building blocks of any software system. Well-structured functions contribute significantly to code readability, maintainability, and testability. Conversely, poorly structured functions can lead to complex, error-prone, and difficult-to-understand codebases. This section explores the characteristics of well-structured functions, focusing on the crucial principle of single responsibility.

Function Size and Structure: The Single Responsibility Principle

The single responsibility principle dictates that a function should have only one reason to change. This means it should perform one specific task, and one task only. A function that adheres to this principle is typically concise, focused, and easy to understand. This improves code readability and reduces the likelihood of introducing bugs when making modifications. Conversely, large, complex functions often violate this principle, leading to several problems.

Anti-Patterns in Function Design

Several anti-patterns frequently lead to overly large and complex functions. These include functions that perform multiple unrelated operations, functions with excessive nesting (deeply nested conditional statements or loops), and functions with excessive length (often exceeding a few dozen lines of code). These anti-patterns hinder readability and make it difficult to understand the function’s purpose and behavior. They also increase the risk of introducing errors during maintenance and updates. Testing such functions becomes significantly more challenging, as individual units of functionality are not easily isolated.

Examples of Functions Violating and Adhering to the Single Responsibility Principle

The following table illustrates functions that violate the single responsibility principle and their refactored counterparts that adhere to it.

| Original Function | Problem | Refactored Function | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Performs multiple operations (validation, calculation, confirmation, inventory update, payment processing) |

|

Improved modularity, testability, and maintainability. Each function has a single responsibility. |

|

Handles multiple shapes, violating single responsibility. |

|

Improved readability and easier extension to support new shapes. |

Best Practices for Writing Concise and Readable Functions

Writing concise and readable functions is crucial for maintaining a clean codebase. This directly impacts the overall maintainability and understandability of the software. Following these best practices will lead to more robust and easier-to-understand code.

- Keep functions short and focused: Aim for functions that are no longer than a few dozen lines of code. If a function becomes too long, consider breaking it down into smaller, more manageable functions.

- Use descriptive names: Choose names that clearly indicate the function’s purpose. Avoid abbreviations or jargon that might not be easily understood by others.

- Minimize parameters: Try to limit the number of parameters passed to a function. Too many parameters can make the function difficult to understand and use.

- Return early or throw early: Avoid deep nesting by returning early from a function or throwing exceptions as soon as an error condition is detected.

- Use comments sparingly but effectively: Comments should explain the *why* of the code, not the *what*. Avoid commenting obvious code.

- Follow consistent formatting: Use consistent indentation and spacing to improve code readability.

Classes and Objects

Source: ebornbooks.com

Classes and objects form the cornerstone of object-oriented programming (OOP). Well-designed classes promote modularity, reusability, and maintainability, leading to cleaner, more robust software. Understanding how to design and organize classes effectively is crucial for writing clean code. This section will explore the principles of SOLID design and their application, along with the benefits of using design patterns.

SOLID Design Principles

The SOLID principles provide a set of guidelines for building flexible and maintainable object-oriented systems. Adhering to these principles reduces code coupling, improves testability, and enhances the overall design. These principles are not mutually exclusive; they often work together to achieve a robust and adaptable system.

- Single Responsibility Principle (SRP): A class should have only one reason to change. This means a class should have only one specific responsibility or job. Violating this principle leads to large, unwieldy classes that are difficult to maintain and test.

- Open/Closed Principle (OCP): Software entities (classes, modules, functions, etc.) should be open for extension, but closed for modification. This principle advocates for extending functionality through inheritance or composition rather than altering existing code. This minimizes the risk of introducing bugs when adding new features.

- Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP): Subtypes should be substitutable for their base types without altering the correctness of the program. This means that a derived class should behave as expected when used in place of its parent class. Violating this principle can lead to unexpected behavior and runtime errors.

- Interface Segregation Principle (ISP): Clients should not be forced to depend upon interfaces they don’t use. This suggests breaking down large interfaces into smaller, more specific ones. This improves flexibility and reduces unnecessary dependencies.

- Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP): High-level modules should not depend on low-level modules. Both should depend on abstractions. Abstractions should not depend on details. Details should depend on abstractions. This promotes loose coupling and makes code more testable and maintainable.

Examples of Well-Designed Classes

Consider a `ShoppingCart` class responsible for managing items added to a shopping cart. It could have methods for adding items, removing items, calculating the total cost, and applying discounts. This class adheres to SRP as it focuses solely on cart management. Further, if we needed to integrate with different payment gateways, we could achieve this through dependency injection, adhering to DIP.

Another example is a `UserAuthenticationService` which handles user login and authorization. This service might use an interface to interact with a database or other authentication providers, exemplifying OCP and DIP.

Examples of Poorly Designed Classes and Improvements

Let’s examine a poorly designed `User` class that violates several SOLID principles:

- Poorly Designed `User` Class: This class handles user data, database interaction, and email notifications. This violates SRP, as it has multiple responsibilities. It might also directly interact with a database, violating DIP.

- Improved Design: Separate the responsibilities into distinct classes: a `User` class for data, a `UserRepository` class for database interaction, and a `NotificationService` class for email notifications. This adheres to SRP and DIP by introducing abstraction and separating concerns.

Benefits of Design Patterns

Design patterns provide reusable solutions to commonly occurring design problems. They offer a structured way to organize classes and objects, improving code readability, maintainability, and reusability. Using patterns such as the Factory, Singleton, or Observer patterns can significantly improve the overall class structure and organization. For instance, the Factory pattern allows for creating objects without specifying their concrete classes, enhancing flexibility and maintainability. The Singleton pattern ensures that only one instance of a class is created, useful for managing resources or global state. The Observer pattern enables loose coupling between objects by allowing objects to subscribe to events, leading to cleaner and more manageable interactions.

Error Handling and Exception Management

Source: cloudfront.net

Effective error handling is crucial for building robust and reliable software. Ignoring errors can lead to unexpected program crashes, data corruption, and security vulnerabilities. A well-designed error handling strategy anticipates potential problems, gracefully handles them, and provides informative feedback to the user or system. This section explores various techniques for managing errors and exceptions in your code.

Error handling involves anticipating potential issues during program execution and implementing mechanisms to manage those issues without causing the program to crash or behave unexpectedly. Exception handling, a specific type of error handling, deals with exceptional events that disrupt the normal flow of the program. These events are typically represented as exceptions, which are objects that encapsulate information about the error.

Strategies for Handling Errors and Exceptions

Several strategies exist for managing errors and exceptions. These strategies vary in complexity and appropriateness depending on the context. Common approaches include using try-catch blocks, returning error codes, logging errors, and employing assertions. The choice of strategy often depends on factors such as the severity of the error, the context in which it occurs, and the desired level of robustness.

Comparison of Exception Handling Mechanisms

Different programming languages provide various exception handling mechanisms. While the specifics differ, the core principles remain consistent. Many languages utilize try-catch blocks, where code that might throw an exception is placed within a `try` block, and the code to handle the exception is placed within one or more `catch` blocks. Some languages also offer `finally` blocks to execute code regardless of whether an exception occurred. The effectiveness of these mechanisms depends on the clarity and precision of the exception handling logic. Poorly designed exception handling can mask errors or make debugging difficult.

Robust Error Handling Techniques

The following table illustrates examples of robust error handling techniques, contrasting them with poor handling approaches:

| Error Scenario | Poor Handling | Improved Handling | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

| File not found | file = open("myfile.txt") (No error check) |

try: |

The improved handling uses a try-except block to gracefully handle the FileNotFoundError, preventing the program from crashing. |

| Division by zero | result = 10 / 0 (Program crashes) |

try: |

The improved handling catches the ZeroDivisionError and prevents a crash, potentially assigning a default value or taking alternative action. |

| Invalid user input | age = int(input("Enter age: ")) (No input validation) |

while True: |

The improved handling validates the input, ensuring that the program receives valid data and handles invalid entries gracefully. |

| Network error | response = requests.get("http://example.com") (No error check) |

try: |

This example uses the `requests` library and demonstrates handling network errors including timeouts and HTTP errors. |

Comprehensive Error Handling Strategy for a Hypothetical Application

Consider a hypothetical e-commerce application. A comprehensive error handling strategy would involve:

* Input validation: Validate all user inputs (e.g., order details, payment information) to prevent invalid data from entering the system.

* Database error handling: Implement robust error handling for database operations (e.g., connection errors, data integrity issues).

* Payment gateway integration: Handle potential errors during payment processing, such as declined payments or network issues.

* Logging: Log all errors with sufficient detail for debugging and monitoring purposes.

* User-friendly error messages: Provide informative and user-friendly error messages to guide users and prevent confusion.

* Exception handling: Utilize try-catch blocks to handle exceptions gracefully, preventing application crashes.

Testing and Code Maintainability

Clean code isn’t just about readability; it’s also about maintainability and reliability. Thorough testing plays a crucial role in achieving both. Without robust tests, even the cleanest code can become brittle and prone to errors when modified. Testing ensures that changes don’t introduce unintended consequences and that the code continues to function as expected. Furthermore, well-structured tests act as living documentation, illustrating how the code should behave and making it easier for others (and your future self) to understand.

Testing methodologies are essential for ensuring code quality. They provide a structured approach to verifying that different aspects of the software function correctly. The choice of methodology depends on the complexity of the system and the specific aspects being tested.

Unit Testing

Unit tests focus on individual components of the code, such as functions or methods. They isolate each unit and verify its behavior in isolation. This approach helps identify bugs early in the development process, before they can propagate to other parts of the system. Effective unit tests are typically small, focused, and easy to understand.

- Example: Consider a function that calculates the area of a circle. A unit test would provide various inputs (radii) and assert that the calculated area matches the expected value using a known formula (πr²).

- Example: A unit test for a function that validates email addresses might test various valid and invalid email formats, ensuring that the function correctly identifies them.

Integration Testing

Integration tests verify the interaction between different units or modules. They ensure that these components work together correctly as a whole. Integration testing helps identify issues arising from the interaction between different parts of the system, which might not be apparent in unit tests.

- Example: If you have a system with a user interface, a database, and a business logic layer, integration tests would verify that these layers interact correctly. For example, a test might simulate a user submitting data through the UI, verifying that the data is correctly stored in the database and processed by the business logic.

- Example: An e-commerce application might have integration tests that simulate a user adding items to a shopping cart, proceeding to checkout, and verifying that the order is correctly processed and stored.

Refactoring and Code Reviews, Clean code a handbook of agile software craftsmanship

Refactoring is the process of restructuring existing code without changing its external behavior. It’s a crucial aspect of code maintainability. Refactoring improves the code’s design, making it easier to understand, modify, and extend. Code reviews provide a second pair of eyes on the code, helping identify potential issues, improve code quality, and ensure adherence to coding standards.

- Refactoring Techniques: Examples include extracting methods, renaming variables, removing duplicate code, and simplifying complex logic. These techniques enhance readability and reduce complexity.

- Code Review Best Practices: Code reviews should focus on functionality, design, and maintainability. They should involve multiple developers to ensure diverse perspectives and identify potential problems.

Code Formatting and Style

Consistent code formatting and style are paramount for creating clean, readable, and maintainable software. A well-formatted codebase enhances collaboration, reduces errors, and simplifies the understanding of complex logic. Inconsistent formatting, on the other hand, leads to confusion, hinders debugging, and ultimately increases development time and costs.

Code formatting isn’t just about aesthetics; it’s a crucial aspect of software craftsmanship. It directly impacts the readability and maintainability of the code, affecting not only the original developers but also those who might work on the project later. Adopting and adhering to a consistent style guide ensures that everyone on the team understands and follows the same conventions, promoting a shared understanding and simplifying code reviews.

Examples of Good and Bad Code Formatting

The following table illustrates the stark difference between poorly formatted and well-formatted code. Consistent indentation, spacing, and line breaks significantly improve readability.

| Poorly Formatted Code | Well-Formatted Code |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Comparison of Code Style Guides

Various style guides exist to promote consistency in code formatting. PEP 8 is a widely adopted style guide for Python, emphasizing readability and consistency. Other languages have their own equivalent style guides, such as Google Java Style Guide for Java or Airbnb JavaScript Style Guide for JavaScript. While specific rules may differ, the underlying principle of consistent formatting remains universal across all these guides. The key is to choose a style guide and stick to it rigorously throughout the project.

Best Practices for Consistent Code Formatting

Maintaining consistent code formatting requires discipline and adherence to established guidelines. Here are some best practices:

- Consistent Indentation: Use a consistent number of spaces (typically 4) for indentation. Avoid mixing tabs and spaces.

- Meaningful Line Breaks: Break long lines into smaller, more manageable chunks to improve readability.

- Consistent Spacing: Use spaces around operators and after commas to enhance visual clarity.

- Naming Conventions: Follow a consistent naming convention for variables, functions, and classes (e.g., camelCase, snake_case).

- Code Comments: Use comments to explain complex logic or non-obvious code sections, but avoid excessive commenting.

- Use of Linters and Formatters: Integrate linters (like Pylint for Python or ESLint for JavaScript) and formatters (like Black for Python or Prettier for JavaScript) into your development workflow to automatically enforce style guidelines.

Illustrative Examples: Code Smells and Refactoring

Identifying and addressing code smells is crucial for maintaining clean, efficient, and understandable codebases. Code smells are indicators of potential deeper problems within the code, often hinting at design flaws or areas needing improvement. Addressing them through refactoring improves not only the immediate readability but also the long-term maintainability and extensibility of the software. This section will explore several common code smells, provide illustrative examples, and demonstrate refactoring techniques.

Long Method

Long methods often indicate a lack of modularity and can make code difficult to understand and maintain. A long method usually performs multiple distinct tasks, violating the Single Responsibility Principle. Breaking down a long method into smaller, more focused methods improves readability and makes testing easier.

| Code Smell Example | Problem | Refactored Code |

|---|---|---|

|

The processOrder method performs multiple distinct tasks, making it lengthy and difficult to understand. Testing individual components is also challenging. |

|

Duplicate Code

Repeating the same or very similar code in multiple places is a clear indication of a maintainability problem. If a bug is found, it needs to be fixed in all locations, increasing the risk of errors and inconsistencies. Refactoring involves extracting the duplicated code into a separate method or class.

| Code Smell Example | Problem | Refactored Code |

|---|---|---|

|

The calculation of the area is duplicated. Changes to the formula require modification in two places. |

|

Large Class

Classes that are excessively large and handle too many responsibilities violate the Single Responsibility Principle. This leads to code that is hard to understand, test, and maintain. Refactoring typically involves breaking down the large class into smaller, more focused classes.

| Code Smell Example | Problem | Refactored Code |

|---|---|---|

|

The User class does too much. It’s difficult to understand, test, and maintain. |

|

Step-by-Step Refactoring Process

A systematic approach is vital when refactoring code with multiple smells. Consider this example: a method calculating order totals with nested loops and duplicated code for different order types.

1. Identify Code Smells: Begin by identifying the existing code smells. In this case, we have a long method, potentially containing duplicated code for different order types.

2. Prioritize Smells: Prioritize based on impact. In this example, extracting the duplicated code might be tackled first to improve readability and reduce risk.

3. Small, Incremental Changes: Refactor in small, easily reversible steps. Extract the duplicated code into a separate method. Thoroughly test after each step.

4. Introduce Meaningful Names: Use clear and descriptive names for new methods and variables to enhance understanding.

5. Test Thoroughly: Testing after each step is critical to ensure the refactoring doesn’t introduce bugs. Unit tests are highly beneficial here.

6. Iterate: Repeat steps 3-5 until all significant code smells are addressed. This iterative process ensures manageable changes and minimizes risk.

The benefits of refactoring extend beyond improved readability. Refactored code is generally easier to maintain, debug, and extend, leading to reduced development time and costs in the long run. It also improves the overall quality and robustness of the software.

Outcome Summary

Mastering clean code is a journey, not a destination. This exploration of “Clean Code: A Handbook of Agile Software Craftsmanship” has highlighted the crucial role of readability, maintainability, and testability in creating robust and sustainable software. By adopting the principles discussed – from meaningful naming and well-structured functions to robust error handling and effective testing – developers can significantly enhance their coding skills and contribute to projects that are easier to understand, maintain, and extend. The ultimate reward is code that not only works flawlessly but also serves as a testament to the craftsmanship and dedication of its creators.